This article was featured in Eurofish Magazine 5 2025.

While global fisheries landings have remained stable for decades, the volume of fish and seafood on the world market has been steadily increasing due to the rise in aquaculture production. In theory, it could be significantly higher, as valuable material is wasted and lost at every stage of the processing chain, from the point of origin to the plate. This indicates untapped potential that can still be harnessed.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), global fisheries and aquaculture production reached a record high of 223.2 million tonnes in 2022, worth a record USD 472 billion. However, this data also includes algae and aquatic plants, which can distort the picture. Nevertheless, the production of aquatic animals alone reached a record level of 165 million tonnes in 2022. This means that since 1961, the available quantity has grown almost twice as fast as the world’s population. In 1961, the global per capita availability of fish and seafood was just 9.1 kg per year, whereas by 2022, it had risen to an estimated 20.7 kg. This is in stark contrast to the predictions of empty seas and the imminent collapse of fish supply. Equally exaggerated are the claims regarding non-food uses, i.e. the proportion of seafood that is not used directly for human consumption. In 2022, it continued to decline, reaching only 20.8 million tonnes. Around 83% of this was used to produce fishmeal and fish oil. The fact that fishmeal and fish oil volumes have remained almost the same is mainly due to the increased use of slaughterhouse waste and other by-products. They accounted for 34% of fishmeal production and 53% of fish oil production. The main conclusion is positive: significant progress has been made in the trend towards the full utilisation of fish and seafood for human nutrition.

‘Food loss and waste’ refers not only to inexpensive and less popular species,

but also to popular and high quality fish.

Accordingly, the outlook for fish supply in the coming years is optimistic. According to FAO experts, it is expected to increase by 10% to 205 million tonnes by 2032. This will be mainly due to the expansion of aquaculture production to 111 million tonnes, but fisheries will also contribute 94 million tonnes. With this solid foundation, annual per capita consumption is expected to increase to 21.3 kg on average by 2032. And this will happen worldwide, on all continents. The only exception is Africa, particularly sub-Saharan Africa, where there are concerns about a potential decline in seafood consumption. According to the FAO, there are likely to be other significant shifts in the global seafood market. Rising incomes, urbanisation and changing dietary trends in many parts of the world are already having a significant impact on global trade flows. For example, the combined consumption of aquatic food products in Europe, Japan and the US fell from 47% to 18% of the total market between 1961 and 2021. Over the same period, the market shares of China, Indonesia and India rose from 17% to 51%. Since these countries are also major seafood producers, this is expected to have significant implications: while global exports of aquatic products accounted for 38% of total production in 2022, their share is projected to decrease to 34% by 2032.

Estimates instead of hard data

As impressive as these figures and the forecasts derived from them may be, much of it is unfortunately based on speculation. This is because the database lacks completeness, accuracy and thus reliability, a shortcoming that more or less limits the credibility of some FAO forecasts. For example, in 2022, around half of the 208 countries with aquaculture production did not report any data to FAO. The ratio of non-reporting producers to total producers was 27:52 in Africa, 25:48 in the Americas, 22:48 in Asia, 8:40 in Europe and 17:19 in Oceania. Due to a lack of reports, the FAO could only provide approximate estimates for the corresponding data in these cases. For aquatic animals alone, this amounted to 13.3 million tonnes, and for algae to 736,900 tonnes.

Weight of discards in the North Sea and Baltic Sea from 2000 to 2019 (in 1,000 tonnes).

Although these statements refer only to aquaculture, it can hardly be assumed that the situation in fisheries could be fundamentally different. Especially since there is an even greater risk that even the official reports contain some inaccuracies and errors. The sea is known to be wide and the night is dark, making control difficult. Small-scale, subsistence and recreational fishing cannot be fully and comprehensively monitored. There is also illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing, the black catches of which can only be roughly estimated. Transhipments at sea are as difficult to monitor as landings in foreign ports, making it difficult to collect data on catches and trade statistics. Some countries do not even have vessel registers, which seriously undermines the quality of catch statistics. Missing, incomplete and poor quality data obscure the true situation and often result in erroneous assessments of the performance of fisheries and aquaculture.

Food loss is an untapped reserve

Despite these difficulties, the FAO is the only reliable source of global fisheries and aquaculture statistics. Its FishStat database is mainly based on annual data from national sources. Where national reports are missing or contain insufficient or contradictory data, FAO experts estimate the figures based on the best available sources using recognised methods. This does not rule out minor errors but does allow for basic conclusions and statements to be made. One of these, for example, is the depressing realisation that, in total, up to 35% of global fisheries and aquaculture production is lost annually on the way to and from the end consumer. Therefore, the target of a 10% increase in fish and seafood production by 2032 could potentially be achieved right now if we succeeded in eliminating the unnecessary waste of more than one-third of these valuable resources. The UN’s Sustainable Development Goal SDG 12.3 therefore calls on the international community to halve post-harvest losses in production and supply chains by 2030. It is an understandable and reasonable demand, but it requires enormous effort to implement. This is because reductions do not depend on a single factor or a single change, such as the introduction of more efficient technologies. Minor errors and inefficiencies occur almost everywhere in value chains and contribute to these losses.

While the bycatch rate for many pelagic fish species fluctuates on average by only two per cent,

in shrimp fishing it can reach almost 90% in extreme cases.

A complex approach is needed that not only holds politicians and legislators accountable, but also requires the expansion of the required capacities and takes into account technological advances and socio-economic aspects. In order to develop appropriate strategies to reduce food loss and waste (FLW), a careful analysis of the baseline situation is needed first:

• Where and when does FLW occur?

• What are the reasons for this?

• How extensive is the waste and what are the economic consequences?

• Which stakeholders and interest groups are most affected?

Discard information is often speculative

Previous studies in this area have shown that the FLW rate can be reduced not only by minimising physical losses of fish in the processing chain, but also by making better use of fish by-products and their nutrients. Fish by-products can be used, for example, for fish silage or feed and fertiliser. They are rich in protein and often contain an abundance of essential amino acids. Some ingredients can be used as additives in the food industry, pharmaceuticals, cosmetic products, or in the manufacture of clothing and leather products. Even recycling as biodiesel is still more sensible than environmentally damaging dumping.

Material and value losses occur to varying degrees at all levels of the processing chain.

When it comes to the waste of resources, bycatch and discards in fisheries are the first things that come to mind for many. Every year, 90 million tonnes of fish are caught worldwide. However, as is well known, this is only a fraction of the actual catch, as most fisheries also have unwanted bycatch, sometimes referred to as secondary catch, in addition to the target species, no matter how selective the fishing gear is. A significant proportion of this has been and is being dumped back into the sea, thus being lost to alternative uses. Discards affect not only of bycatch species, but sometimes also target species, for example if they are too small, in poor condition or difficult to market. Sometimes there is simply not enough space on the fishing vessel to take the catch on board.

Separate collection of the individual components is often a prerequisite for

the economic use of slaughterhouse waste and by-products.

For a long time, bycatch and discards were largely overlooked in fisheries assessments. However, as environmental awareness has grown and concerns about overfishing and sustainability have gained increasing public attention, the issue has become a significant topic of focus. It has now been argued that this is a waste of resources, when attempts were made to quantify the biological, ecological, economic and cultural impacts of discards. If catch and landing volumes cannot be determined accurately, this is even more impossible for bycatches and discards. Based on the little data available at the time on the subject, Alverson et al. 1994 (FAO. No. 339) estimated that bycatches and discards from commercial fisheries range from 17.9 to 39.5 million tonnes per year (average 27.0 million tonnes). The wide range of figures alone shows how uncertain the authors themselves were in their estimates. Nevertheless, an initial estimate was now available and understandably caused a stir. Around 40% of the world’s catch is thrown back into the sea, dead or dying. The study proved useful to NGOs critical of the fishing industry, and they have since used it as an argument to accuse the industry of being wasteful and overly driven by profit. Especially since the economic losses, which probably amounted to many billions of dollars, were compounded by ecological damage that could hardly be quantified.

Landing requirement is also controversial

Regardless of the polemics and populism, bycatch and discards are more than just a nuisance. They distort the stock assessment database and are a source of error in the calculation of fishing quotas. As a result, since the 1990s, bycatch recording has become a focus of research in fisheries biology, leading to somewhat more accurate estimates. Observers travel on fishing vessels and collect data. In addition, electronic technologies are employed to monitor fishing activities, and logbook data, along with voluntary information from fishers, is collected. This has significantly improved our understanding of the situation at sea, although there are still some areas where the data is still rather inaccurate and speculative. Based on data from 1992–2001, Kelleher (2005) estimates that an average of 7.3 million tonnes of fish are discarded worldwide. Discards vary considerably by region, species and fishing method.

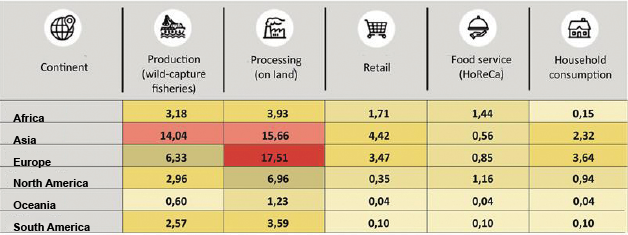

Percentage loss of edible aquatic food worldwide by continent and at key nodes in the value chain.

Even this much more reliable figure is not accepted by everyone. Some believe it to be relatively close to reality, while others doubt the figures and suspect that they are too low. However, it cannot be denied that discards have fallen in recent years due to more selective fishing gear, changes in regulations and better use of bycatch. The EU’s fisheries policy also aims to end wasteful discarding practices and introduced a landing obligation in 2015, which has been in force since January 2019. Since then, the principle of ‘you catch it, you keep it’ has applied. All catches from stocks subject to a catch quota (TAC) must now be landed. However, the consequences of this requirement seem to have made some former critics change their views. In particular, ornithologists among conservationists are now warning that a ban on discarding fish at sea could also harm the marine environment, because other species now lack a food source. North Atlantic seabird populations are already declining, and the lack of food is tempting skuas to snatch puffin prey. The previously criticised ‘waste of resources’ is correct from an economic point of view, but for natural ecosystems, the discard is by no means ‘waste’. The total energy is preserved as the discarded fish serve as food for other animals, such as seabirds and crabs. Some authors also point out that bycatch in nets is often made up of predators of the target species. They follow their prey, so the simultaneous removal of prey and predators somehow balances out their relationship in the ecosystem.

Many options for solving the problem

The second largest source of losses in the value chain after discards is the processing of fish on board fishing vessels and on land. A considerable proportion of the catch is lost through gutting, deheading, filleting, trimming and skinning. Whether it ends up as waste or is recycled in a meaningful way depends on several factors. Cultural and geographical differences also play an important role. The demand of regional markets and the dietary preferences of local consumers also influence the type and quantity of waste. In general, in countries with higher incomes, convenient and easy-to-eat products such as fillets or loins are preferred, which reduces the yield of fish parts consumed. By contrast, in countries with lower incomes, people tend to eat whole fish. It is less wasteful than consuming semi- or only partially processed products. Nevertheless, when all factors are taken into account, Asian countries still account for the highest post-harvest losses of aquatic food, at 37%. This is not due to consumption, but to losses during transport and storage. Europe is close behind, with almost a third. At the other end of the scale is Oceania, where, according to FAO data, less than 2% of the edible portion of fish and seafood is lost.

Unlike in rich industrialised countries, where fillets and loins are preferred,

fish in other parts of the world is often prepared whole.

Food losses occur at almost every level of the processing chain. A 2021 report by the World Economic Forum estimates that we lose around 10–12 million tonnes of fish and seafood each year due to lack of refrigeration, improper storage or processing errors. Other sources put the loss of edible aquatic food as high as 23.8 million tonnes. These are only rough estimates, but they show the scale of the problem. Basically, all areas of the chain are affected, albeit to varying degrees. This ranges from excessive transport times and incorrect storage without adequate cooling to pest infestation that renders fish products unusable in many parts of the world. It is estimated that sun-drying alone accounts for around 30% of the world’s fish losses due to infestation by blowfly and beetle larvae. Not only is there a lack of know-how and suitable processing technology for handling and preservation on board and on land, but also quite often a lack of the general logistical conditions. In some areas, the power supply is unstable or even non-existent. Access to hygienic drinking water is not guaranteed everywhere, and the poor state of the road network complicates and delays the transport of perishable goods. Lack of cold storage makes it difficult to maintain a continuous cold chain, often requiring indirect methods to preserve the product. In retail, losses occur when a fish is not sold in time and exceeds its sell-by date.

These few examples show that good intentions and greater care on the part of those involved are not enough. Massive investments are needed to reduce food loss and waste. This is especially true for fish and seafood products, which are among the most widely traded foodstuffs worldwide, and which require appropriate logistical conditions. According to FAO forecasts, 181 million tonnes of aquatic food will be traded and consumed annually worldwide at the regional, national and international level by 2030. The more often a product is reloaded and temporarily stored en route from the producer to the end user, the higher the risk of damage or spoilage. Even in professional restaurant kitchens, fish and seafood are sometimes lost due to improper handling or human error in preparation. Despite taking great care, millions of ambitious amateur chefs in home kitchens also experience this. Reducing fish losses therefore remains an ongoing challenge for all of us.

Manfred Klinkhardt