This article was featured in Eurofish Magazine 6 2025.

The picture painted by print, television, and other mass media of the future of our oceans and fisheries is bleak: destroyed ecosystems, depleted stocks, and empty seas. Anyone seeking reliable information should instead read the report Agricultural Outlook 2025–2034, in which the OECD and FAO look ahead to the coming decade—and despite some problems, their assessment is more optimistic.

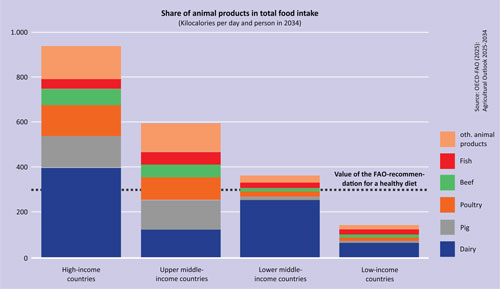

On a regular basis, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) assess markets for agricultural commodities and fish, and forecast likely developments to provide policymakers with a sound basis for decisions. On 15 July 2025, the OECD and FAO published the 21st edition of this analysis, Agricultural Outlook 2025–2034, according to which consumption of animal-based foods is likely to rise particularly in middle-income countries. There, analysts expect growth of a hefty 24 percent—four times the global average. Despite this increase, the share of animal-based foods in daily caloric intake remains low in middle-income countries, averaging 364 kcal per person, only just above the FAO’s recommended 300 kcal per day. In low-income countries, 143 kcal does not even reach half the benchmark for a healthy diet.

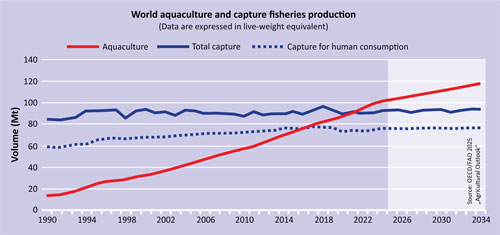

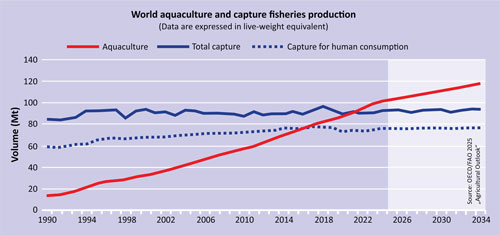

Taken together, global agricultural and fisheries production is expected to grow by 14 percent by 2034. The contribution made by fisheries and aquaculture is greater than many media forecasts suggest. In 2024, they produced a combined 193 million tonnes of fish, crustaceans, and other aquatic animals, and this volume is expected to rise to 212 million tonnes by 2034. Despite this increase, production growth is likely to slow. By 2034, analysts expect growth of 12 percent. The increase in fish supply is mainly due to aquaculture. Although its growth rate is also expected to slow by 2034, aquaculture is projected to account for 56 percent of total output over the outlook period, delivering more aquatic animals than capture fisheries.

Total production of aquatic animals set to keep rising

Landings from capture fisheries are also likely to increase, but only modestly. After the El Niño-related low anchovy catches in Peru in 2023, they have recovered and are expected to stabilise at 94 million tonnes by 2034. Nonetheless, volatility in fisheries remains high because they can be affected by hard-to-predict events. Production declines of roughly 2 million tonnes are expected, for example, in 2027 and 2031 if the forecast El Niño events do in fact occur. This leads to lower anchovy catches and thus reduced supplies of fishmeal and fish oil, which also affects feed availability for aquaculture.

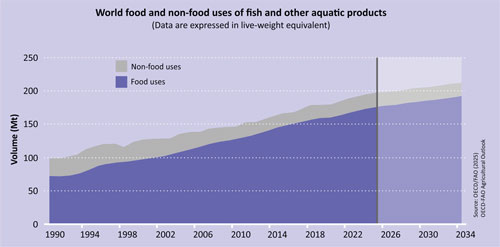

The share of non-food uses in total fish supply is declining slowly but steadily.

By 2034, they are expected to account for only about 10 percent.

Even so, the OECD-FAO Outlook assumes that global aquaculture production will reach an expected 118 million tonnes (aquatic animals only) by 2034. That would be a 20 percent increase over the average for 2022 to 2024, well below the 51 percent of the previous decade. According to the study, the reasons for the weaker growth are stricter environmental regulations and the shortage of suitable production sites globally. Although the growth rate of Asian aquaculture is expected to slow sharply in the next decade, the continent is estimated to account for 88 percent of total production in 2034. China maintains its position as the world’s largest producer. Emerging aquaculture nations, especially India and Vietnam, are expected to significantly expand their contribution to global output. Production increases are likely to be particularly strong for shrimp (+38 percent), freshwater and diadromous fish (excluding carp and tilapia) (+29 percent), and salmonids (+26 percent).

More fish for human consumption

The OECD-FAO Outlook forecasts a rise in global per-capita consumption of fish and seafood from 21.1 kg in 2022–2024 to 21.8 kg by 2034. There will be regional differences. Per-capita consumption in Africa is expected to decline, especially in sub-Saharan countries. A slight decrease is also expected in Europe. Growth in demand in Asia slows to only 11 percent compared with 32 percent in the last decade. This is also likely to affect non-food uses of aquatic products, especially the production of fishmeal and fish oil. As a result, the shares of food and non-food applications are expected to shift slightly. The food share will rise to 90 percent by 2034. Although per-capita consumption of aquatic foods is likely to grow less strongly in the next decade, it will still increase.

In nominal terms, prices for aquaculture and fishery products are expected to rise by 8.7 percent and 12 percent respectively. In real terms, prices are likely to fall by 13 percent in aquaculture and 10 percent in capture fisheries. The price declines are due to increases in production, as well as competition from other protein sources. Poultry prices are expected to fall over the outlook period. In addition, inflationary pressure could ease by 2034. Changing environmental conditions, mainly because of climate change, geopolitical upheavals in world trade, and a shift towards sustainable production practices in fisheries and aquaculture all influence developments in global trade. This is why compliance with binding rules in the global seafood trade is becoming more important for global food security. No one can yet foresee how China’s policy realignment, with a stronger focus on sustainable practices, will affect future production and what consequences this will have for global market supply. China’s aquaculture is already growing more slowly than in previous years.

Non-food uses continue to decline

Anyone looking for links between fisheries and aquaculture will inevitably come across fishmeal and fish oil, which closely link the two sectors. Catches from fisheries form the basis for the production of fishmeal and fish oil, which in turn are indispensable components in feed for aquaculture—despite the growing share of alternative agricultural raw materials. According to the OECD study, by 2034 an expected 10 percent of total fish and animal-origin seafood will be used to produce fishmeal and fish oil and for other non-food purposes, such as ornamental fish, bait, or pharmaceutical products. Aquaculture remains the largest consumer of fishmeal and is expected to increase its market share to 84 percent by 2034. The forecast assumes that China will account for around 42 percent of global fishmeal use by 2034. Fishmeal output is expected to rise slightly over the next decade to around 5.9 million tonnes worldwide by 2034. However, this is not due to fisheries catches but to the increasing utilisation of processing leftovers, trimmings, and by-products from fish processing. By 2034, an expected 31 percent of fishmeal will come from such “waste”. This trend is driven by rising demand for fish fillets in wealthy countries, which leads to more processing residues. In addition, the feed industry is turning to other components, especially oilseed meals.

While landings from capture fisheries are expected to remain at roughly the same level by 2034,

aquaculture production will continue to rise according to the OECD forecast.

Fish oil production is also expected to recover significantly after the slump in 2023 when Peru’s anchovy catches faltered. The study forecasts an increase to 1.5 million tonnes by 2032. Nevertheless, the supply situation for aquaculture is likely to ease only slightly (by 2034, an expected 59 percent of fish oil will be used by aquaculture), because competition is intensifying with the pharmaceutical industry, which is claiming more and more high-quality fish oil as a dietary supplement for human consumption. Compared with historical values, real prices for fish oil and fishmeal will remain high, but probably below their peaks (2012–14 for fishmeal, 2023 for fish oil).

Climate change threatens the reliability of the forecasts

The OECD and FAO analysts’ forecasts are, however, subject to uncertainties. Environmental changes, amendments to existing regulations, and trade tensions influence production over the outlook period. Fisheries are particularly affected and are already suffering from climate change. Experts fear that usable fish biomass could decline by more than 10 percent in some marine regions by the middle of the century. That would be a serious setback. Short-term changes and extreme weather events—for example, marine heatwaves—affect fisheries production more than longer-term warming trends caused by climate change. This is especially evident in El Niño events in the Pacific, whose frequency, intensity, and duration affect anchovy abundance and thus the production and prices of fish oil and fishmeal, and subsequently aquaculture. Climate change also favours non-native and invasive species. They are spreading into regions where they could not previously survive or reproduce. Such changes are hard to predict and are a source of uncertainty in the Outlook projections.

The nominal price is the going price of a good at the current time. The real price, by contrast, also takes inflation and other price changes into account, and thus reflects the actual value of the good.

Climate effects can probably no longer be averted, but at best mitigated and limited. This would require vigorous climate-protection measures from policymakers, but many governments lack the courage. Regulatory interventions in fisheries and aquaculture are therefore more likely, in order to prepare both sectors for the changes ahead. In fisheries, more flexible management would be helpful to allow certain areas or fisheries to be closed more quickly. In aquaculture, it would probably help to move production sites further from the coasts into open marine areas, where temperature conditions are more stable.

One important measure that is likely to help improve the situation is already on the horizon. After years of negotiations, the World Trade Organization’s (WTO) first agreement to combat overfishing entered into force in mid-September 2025. The agreement prohibits the 166 WTO member states from continuing to subsidise illegal fishing. Governments spend an estimated 22 billion dollars every year on harmful subsidies that contribute to overfishing. There will also be no state aid for the harvesting of already overfished stocks. The subsidy ban applies to all vessels and companies engaged in illegal, unreported, or unregulated fishing (IUU fishing). This includes, for example, prohibited fishing methods that lead to by-catch of other fish. For developing countries and their fishing areas, the rules will not take effect until two years later. However, the fisheries agreement could fail again after a short time. The WTO has announced the goal of reaching a broader agreement against overfishing within the next four years. If these negotiations fail, the new agreement will automatically expire.

Manfred Klinkhardt